This is a narrative of my childhood from the time we lived in Santa Monica, to my young adulthood when I attended UCLA. A few photos are included, and there are links to separate pages of photos.

1961/1962: Move to Santa Monica

When I was in 1st grade – that is, in late 1961 or early 1962—we moved from the high desert to the big city. My father’s employer John Blesch found office space, or perhaps joined a larger firm, in West Los Angeles, in a building at the corner of Wilshire and Barrington, right by the then under-construction Barrington Plaza apartment towers (https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Barrington_Plaza).

(The photo here shows the building which no longer exists; another building is in its place.) My father would later find decades of work with Daniel, Mann, Johnson, and Mendenhall (DMJM, pronounced dim-jim), https://www.laconservancy.org/architects/dmjm, a large architectural firm with headquarter on Wilshire Blvd. west of downtown LA.

(The photo here shows the building which no longer exists; another building is in its place.) My father would later find decades of work with Daniel, Mann, Johnson, and Mendenhall (DMJM, pronounced dim-jim), https://www.laconservancy.org/architects/dmjm, a large architectural firm with headquarter on Wilshire Blvd. west of downtown LA.

My family moved to a rented house in Santa Monica, on 21st Street. In fact, it must have been 2335 21st Street; I deduce that address, not from driving down that street some 10 years ago – I tried, but the houses on that street, amazingly, had all been resized, expanded, or perhaps completely replaced since they were relatively small cottage-like structures 50 years ago, and so were unrecognizable (and all the trees were bigger) – but because I know it was directly up the street from a public library, which I see must be the Fairview Branch, and because it the last house but one from the next northwest cross-street, and because it a had a large combination garage/guest-house at the back, which you can easily see via Google Earth view.

My family moved to a rented house in Santa Monica, on 21st Street. In fact, it must have been 2335 21st Street; I deduce that address, not from driving down that street some 10 years ago – I tried, but the houses on that street, amazingly, had all been resized, expanded, or perhaps completely replaced since they were relatively small cottage-like structures 50 years ago, and so were unrecognizable (and all the trees were bigger) – but because I know it was directly up the street from a public library, which I see must be the Fairview Branch, and because it the last house but one from the next northwest cross-street, and because it a had a large combination garage/guest-house at the back, which you can easily see via Google Earth view.

This was an utterly different environment from the desert of Apple Valley. We were two miles from the ocean (10 streets per mile); the weather was cool, often foggy; the back yard was full of Birds of Paradise plants, succulents, and snails. I walked to Grant Elementary School, half a mile northeast, and I was allowed to walk down 21st to the library, the first library I’d been to, where I explored the children’s section and wondered about the other larger, darker, further sections of the library. Whatever books those were, they must have been the first books I read. (My parents later acquired set of encyclopedia and whatnot, but never other books—there were never Dr. Seuss and any other picture books in the house when I grew up.)

This move marked the first of many school changes in my life, including a couple mid-year transfers, which were never easy. (From Kindergarten through 12th grade, I attended 8 different schools, whereas a child living in the same place for that time, in any area of the US at least, would attend 3.) I remember feeling abandoned, even betrayed, when my mother left me at the new school, Grant, that first morning. I did OK, probably not well. I remember that yo-yos were all the rage among 1st graders at the time. I never got the hang of them.

This move marked the first of many school changes in my life, including a couple mid-year transfers, which were never easy. (From Kindergarten through 12th grade, I attended 8 different schools, whereas a child living in the same place for that time, in any area of the US at least, would attend 3.) I remember feeling abandoned, even betrayed, when my mother left me at the new school, Grant, that first morning. I did OK, probably not well. I remember that yo-yos were all the rage among 1st graders at the time. I never got the hang of them.

Meanwhile, while my father’s family never left Illinois (and their descendants are still there), my mother’s relatives drifted to California as we did. My mother had only one sibling, a younger brother, Robert (my Uncle Bob). He also served in the military, but I know no details; but after that, for whatever reason, he ended up in southern California, where he married a woman named Dorothy, and had a daughter, Paula, just a few months older than I. (My Uncle Bob soon thereafter divorced Dorothy when he realized he was homosexual, and lived a long life with his partner Mark Mandell, though until the day he died his family never acknowledged or perhaps simply never understood that relationship.) My maternal grandmother, having been effectively abandoned by her children for California, made the move herself to be with us all. She lived for a time in the Apple Valley apartment my own parents lived in for a while; then she moved to Costa Mesa, perhaps where my Uncle Bob was living; and then when we found the Santa Monica house with the guest house, she moved in with us.

She lived in the guest bedroom attached to the garage. I recall that on Friday nights, when “The Flintstones” was on TV, I would ‘camp out’ with her in her room, watching the show, and sleeping over. (I was 6 or 7 years old.)

Summer 1962: Move to Reseda

We were in Santa Monica only six months. Over the subsequent summer, 1962, my father bought a house, and we moved out of the rental. The new house was in Reseda, in the San Fernando Valley, over the Santa Monica Mountains north of Santa Monica and West LA, but still mostly part of the city of Los Angeles (the exceptions were the cities of Burbank and San Fernando, and to the east, the city of Glendale, technically not part of the valley). It’s a large valley to be urban; some 10 miles by 15 miles, almost completely filled by grids of north/south west/east major streets and half mile intervals with residential streets in between. In 1962 there were still orange groves in many spots; scenes in the film Chinatown (set earlier) show some of those.

Grammie in Apple Valley

My grandmother then moved into the house in Apple Valley, which over the period my family stayed in Santa Monica, my father had been unable to sell. I have no recollection of how that played out at the time. How she must have felt, moving from a small town in Illinois, so moist and green and congenial, to a series of temporary apartments and guest houses in the Los Angeles basin, then to a dry desert home in Apple Valley, 100 miles from her children down in LA. As far as I could tell over the subsequent years, she did fine. She got a job with a local community services agency, as a receptionist; she became active in a local church (which one I don’t know, except that it was in neighboring Victorville). She lived until 1984 (age not quite 84). (All my grandparents were born in 1900, or a year or two later.) For all the time my family lived in LA, excepting a three-year relocation to Illinois, visiting “Grammie” in Apple Valley was a routine, monthly, weekend trip. Even after I moved out on my own, in 1978 when my parents and younger siblings moved to Tennessee, I had Apple Valley to visit, on my own or with my Uncle Bob. And so my personal relationship with Apple Valley lasted until I was 30 years old, until Uncle Bob, who owned the house by then, finally sold it two years after my grandmother’s death, in 1986.

My grandmother then moved into the house in Apple Valley, which over the period my family stayed in Santa Monica, my father had been unable to sell. I have no recollection of how that played out at the time. How she must have felt, moving from a small town in Illinois, so moist and green and congenial, to a series of temporary apartments and guest houses in the Los Angeles basin, then to a dry desert home in Apple Valley, 100 miles from her children down in LA. As far as I could tell over the subsequent years, she did fine. She got a job with a local community services agency, as a receptionist; she became active in a local church (which one I don’t know, except that it was in neighboring Victorville). She lived until 1984 (age not quite 84). (All my grandparents were born in 1900, or a year or two later.) For all the time my family lived in LA, excepting a three-year relocation to Illinois, visiting “Grammie” in Apple Valley was a routine, monthly, weekend trip. Even after I moved out on my own, in 1978 when my parents and younger siblings moved to Tennessee, I had Apple Valley to visit, on my own or with my Uncle Bob. And so my personal relationship with Apple Valley lasted until I was 30 years old, until Uncle Bob, who owned the house by then, finally sold it two years after my grandmother’s death, in 1986.

Living in Reseda

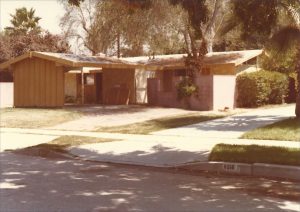

The Reseda house and neighborhood was the most utterly typical suburban place we ever lived. It was at 6516 Rhea Avenue, in the center of the western half of the San Fernando Valley, and sheltered by several turns from the busy Reseda and Victory Boulevards. It was on a street of similar homes built in the 1950s. Smallish by today’s standards, it was 1200 square feet with four bedrooms and two baths. No garage, just a carport. (Photos on another page here, from 1964). There was a backyard with grass and a cement patio, and trees in the corners.

We had only one car, which my father drove to work. So my mother was, necessarily, a stay-at-home mom. I shared a bedroom with recently born baby brother Kevin; Sue and Lisa shared a bedroom; my parents had a bedroom; and the fourth was given over to my father’s at-home office. He constructed an L-shaped desk built on steel girders with walnut-finished plywood tabletops, and two bookcases mounted on the extended upright girders at the back corners; at the bottom of each bookcase was mounted a florescent light. It was very sturdy, and was built to be easily disassembled and reassembled. My father was quite the home handy man. (He never did much work at home, though, and with moves to Illinois and then back to California, he rebuilt the desk as a single rectangle with one bookcase/light fixture and it became the desk in my bedroom.)

We had only one car, which my father drove to work. So my mother was, necessarily, a stay-at-home mom. I shared a bedroom with recently born baby brother Kevin; Sue and Lisa shared a bedroom; my parents had a bedroom; and the fourth was given over to my father’s at-home office. He constructed an L-shaped desk built on steel girders with walnut-finished plywood tabletops, and two bookcases mounted on the extended upright girders at the back corners; at the bottom of each bookcase was mounted a florescent light. It was very sturdy, and was built to be easily disassembled and reassembled. My father was quite the home handy man. (He never did much work at home, though, and with moves to Illinois and then back to California, he rebuilt the desk as a single rectangle with one bookcase/light fixture and it became the desk in my bedroom.)

We acquired both a cat and a dog. The cat was a purebred Siamese. Her name was Tuppy, short for Tup-Tim. She was mostly gentle—she would lie on my pillow at night and lick my very-short-haired head—but in a disturbing incident, she had kittens (did my father have her bred, or was it by accident? Was she an indoor/outdoor cat? I don’t remember) and dismembered most of them when they were all isolated in the office. I don’t know why a mother cat would do that, and have never heard of it happening again. When we moved to Illinois, we left her with Grammie in Apple Valley, but she soon ran away and never returned.

We had a dog, a pure-bred Samoyed – I specifically remember a family trip all the way to, I think, Long Beach, to an appropriate kennel – named Tina, short for Chatina-of-the-Igloo. He was always delightful, though he barked too much. He moved with us to Illinois, then back to California, then with the family when they moved to Tennessee in 1978.

I walked to school, to Vanalden Avenue Elementary school, west on Victory and south on Wilbur, about half a mile. (I walked down along Erwin more often than not, then lined by eucalyptus trees and without sidewalks.) I attended 2nd through 6th grades there. It was a school, typical of those in California, consisting mostly of two-room bungalows, with steps to each front door, with only the administrative section – offices, library, cafeteria — built as a permanent structure. I was a good student, close but at the top of each grade class. (I still have all my report cards—mostly As, a few Bs, rarely a C.) There I learned the multiplication tables, did a special report about the country of Peru, and participated in an extracurricular square dance class, where I was, by random selection, selected president. I was co-lead in the sixth grade class play, playing a prince. At the end of sixth grade we held, not a graduation, but a “culmination,” which involved students putting on performances for the parents, including some kind of Russian dance with an alternating skip move, that I did better than anyone else (I had practiced at home). In elementary school we had “recesses” of course; the playground was covered in asphalt and laid out with dodge ball courts, tether ball squares, and hopscotch grids. I always hated forced participation in games, especially dodge ball, but managed hopscotch OK.

One other elementary school memory: for a Halloween party at school, my family dressed up as the Addams Family https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/The_Addams_Family_(1964_TV_series), mimicking the characters from the TV show. My parents were Mr. and Mrs. Addams; my Uncle Bob played Lurch; I was Cousin Itt, covered by a sheet with lengths of yarn attached, made by my mother. (Or was that the time my father played “Goldfinger,” and you couldn’t guess who he was playing because he kept his hand with the gold-painted finger in his pocket all the time? Until he revealed it.)

1965-1968: Cub Scouts and Boy Scouts

My father was always anxious for me to be more of a real boy. In Reseda he had me try to climb a tree in our back yard, and I couldn’t do it. (I was uncoordinated.) He wasn’t himself an outdoorsy person – more of a home project guy, as mentioned – but  somewhere around 1965, 5th grade, he took me on a two-person camping weekend in our new Chevelle Station Wagon. In a quick three-day weekend we drove from LA to Zion National Park, then Bryce, and then to the north rim of the Grand Canyon. I had gotten my very own camera, a Kodak Instamatic, and still have a handful of square, black and white prints from that trip. We probably slept in the car; certainly staying at a motel was not the kind of thing my father would do; that would have been presumptuous.

somewhere around 1965, 5th grade, he took me on a two-person camping weekend in our new Chevelle Station Wagon. In a quick three-day weekend we drove from LA to Zion National Park, then Bryce, and then to the north rim of the Grand Canyon. I had gotten my very own camera, a Kodak Instamatic, and still have a handful of square, black and white prints from that trip. We probably slept in the car; certainly staying at a motel was not the kind of thing my father would do; that would have been presumptuous.

An opportunity for me to man-up came when our neighbors, those Strausers, moved in, and had some involvement with Boy Scouts. And it happened about the same time that a Cub Scout “den” met once a week at the house on the other side of us from the Strausers. (If I recall correctly, cub scouts, for boys of age 8 to 11, would meet weekly after school at the home of a “den mother,” and perhaps do occasional outings. We wore blue uniforms with yellow neckerchiefs. You learned skills and crafts and earned badges, ideally about one a year, for the ranks Wolf, Bear, and Lion, and finally a culminating award called “Webelos,” which was the equivalent of being a Tenderfoot in Boy Scouts, once you were of age.) I was firmly encouraged to join the Cub Scouts next door, belatedly, around age 10 I think, and managed to earn Lion and Webelos without needing to earn the earlier two ranks.

Glancing around the internet, I also now remember I received an “Arrow of Light,” an award for some set of achievement that gave you a white sash, embroidered with a red arrow, to wear diagonally over your uniform. I would have remembered that was a Boy Scout thing, but apparently not, says the interwebs. What I do remember, now that I think about it, is that the selection of which boys would get it was held at a camp outing, at night, with all the boys standing in a circle around a big bonfire. Perhaps there was music or chanting. And then, without warning, someone behind you in the darkness would shove you forward, into the center by the bonfire, to indicate your selection. These scouting programs were very hierarchical and ceremonial, and more than occasionally mystical.

I remember very little about those Cub Scout meetings, but I remember much more about being a Boy Scout, even though I was a scout there in Reseda for only a little over a year before we moved to Illinois. In Boy Scouts you join a “troop,” meet weekly in the evenings at some venue, typically a school or church, and monthly go on campouts led by some contingent of fathers. You wear khaki uniforms, again with neckerchiefs. Each troop had a distinctive neckerchief. I was in Troop 110, who wore Kelly-green neckerchiefs edged with white. You were a Tenderfoot upon entry, then worked through various skills and tasks (for cooking, knot-tying, hiking, forestry, etc.) to earn badges for Second Class, First Class, Star, Life, and Eagle. Along the way, in addition to the basic requirements for each badge, you had to earn specialized “merit badges” on specific topics. A dozen or so of these, on core topics like camping and first aid, were required for the rank badges, while dozens of others were optional depending on one’s interests. (I earned merit badges for astronomy and stamp collecting, I recall.) These special merit badges usually required special meetings at the homes of retired scout leaders who specialized in one subject or another. I remember walking from our house on Rhea Avenue, cross the bridge over the wash—the concrete lined Los Angeles River, usually dry—to the strange remote territory along Yolanda Ave. or perhaps Capps Ave, all of ¼ mile away. I think that was the astronomy mentor.

Troop 110 met at the nearby Junior High School, Sequoia, which I attended beginning the 7th grade. (I think I’d become a boy scout in 6th grade.) We met Monday evenings after dinner in the gymnasium. Most weeks just the boys and a few scout leader fathers attended. The troop was divided into several “patrols,” each with a patrol leader and an assistant patrol leader. At the beginning the meeting, we would line up in parallel rows by patrol, and says the pledge of allegiance and the scout oath. Then we would…what? Practice knot tying or somesuch? Don’t recall the details. Every three months all parents were invited to attend, and that’s when any awards individual scouts had earned since the previous three-month meeting would be awarded. Though I wasn’t as naturally outdoorsy or sporty like most boys that age, I did well proceeding through the ranks (and the merit badges, anything I could approach academically): I achieved Second Class after three months, First Class three months after that, and Star six months later, a year since joining. (And then we moved to Illinois.)

The memorable events of boy scouting were the campouts. I remember 10 or 12 quite vividly, though in retrospect (I’ve tried occasionally over the years, I’ve been able to pin down exactly locations of only a couple of them). Campouts typically began Friday after dinner, scouts and selected fathers gathering at the junior high school to arrange carpools, then driving an hour or two to the location. Then typically, spending all day Saturday at the location, and returning on Sunday morning after breakfast. Each boy brought his sleeping bag; the troop had a set of two-person tents, and larger tents for groups of leaders. The troop must have arranged provisions, and the scouts would cook meals over campfires.

- My very first was at a campground way up Big Tujunga Canyon, right along the river. It began raining Saturday night, and we had to pack up early Sunday morning to get out before the dirt road out of the site turned to mud. My father was on this trip; he didn’t accompany most of them.

- Another early event was at a campsite with cabins in the Angeles National Forest, way up in the mountains where there was snow. I was a beginner, and didn’t have the right hiking boots to join the others on a hike.

- Twice, I think, we did hikes, carrying backpacks, from a cul de sac in Altadena up along a graded fire road to Henninger Flats, a property owned by the LA County Fire Department (at least it is now), in the foothills of the San Gabriel Mountains, with facilities and cabins. The second trip had a purpose: we were put to work literally digging ditches to install some kind of plumbing. Work that gave us credit for one of those merit badges.

- Others: out in the desert near Mojave, where we dug for jade; a camp in the hills above Malibu where one boy tripped and slit his throat open on a tent peg; on the beach at Carpinteria, where the restrooms were filthy beyond imagination; one at Devil’s Punchbowl, another where we had to leave early Sunday because of rain; one at Apple Valley’s Lone Wolf Colony (https://www.lonewolfcolony.org/).

- And the big one was a week-long summer stay at Camp Whitsett (https://www.campwhitsett.org/), a dedicated Scout Camp in the southern Sierra Mountains. A whole week. This must have been summer 1967, between my 6th and 7th We slept outdoors, in our sleeping bags on groundcovers, without tents. My memories of this is that I did not participate in the naked mile-swim in the lake (which older boys did to earn some merit badge), and that one day we practiced shooting guns at a gun range, it being the first and only time in my life I’ve fired a gun. I wasn’t a natural.

More later about Boy Scouts in Illinois. While compiling this essay I remembered that I still have a box of scout paraphernalia — badges and sashes — in the back of my closet. So I took photos of them, on this page: link.

Fall 1967: Junior High

For 7th grade I attended Sequoia Junior High School, along Victory between Yolanda and Reseda Blvd. (but its facilities are now apparently occupied by something called “Sherman Oaks Center for Enriched Studies” according to Google Maps, in March 2020). Junior High, at least at that time and place, was when you enrolled in various classes with different teachers: a math class, and English class, and so on. Since we moved away to Illinois in early 1968, I didn’t finish the grade there, and I have only a couple specific memories of Sequoia. One was that there was now a separate “Physical Education” course, with locker rooms, gym clothes, and showers! You see other boys naked—and they see you! No, I’m not going there. I was pudgy and had oddly puffy nipples; they were mortifying; other kids made fun of me. (This condition has waxed and waned over my entire adult life.) There was an outdoor weightlifting area, with equipment and benches on gravel. I was OK there, actually. But we had a test for how far we could throw a softball. My performance was lame. I was “uncoordinated.” You’d think PE teachers would understand the range of physical abilities among all their students, but my impression, from then through high school, was that PE teachers would roll their eyes in contempt at any subpar performance. To PE teachers, your ability to play sports and perform athletically was the only measure of a boy’s worth.

The second specific memory is that, perchance, I enrolled in a “drafting” class, perhaps an odd course offering for 7th grade, but there it was. The course consisted of learning how to draw precise plans, along each of three dimensions, of objects shown to us three-dimensionally. No wait, we would get plans of an object from two dimensions and have to deduce the plan for the third. Remember, my father was an architect, where such drawings are required to construct physical buildings. I was actually pretty good at doing such drawings, until near the end of the semester when the example objects became paradoxical. My father was actually was impressed by my success in this class, but he also told me, never become an architect. (I gather his early ambitions were idealistic and never fulfilled; he eventually worked many years designing industrial support buildings, the least glamorous projects you could imagine.)

Spring 1968: Illinois — Cambridge

In 1968, with his mother’s failing health in his hometown of Cambridge, Illinois (she died of Parkinson’s Disease within a year), my father got a new assignment with DMJM (which had nationwide and international concerns) and we relocated to Illinois. The move was relatively abrupt, in the middle of a school year, when I was halfway through seventh grade. Of course we had relatives to stay with in Cambridge—the reason for the move was to be near them—a two- or three-hour drive from my father’s new job in suburban Chicago. (He worked infrastructure design for the industrial buildings that supported the big particle accelerator in Batavia, that later became known as Fermilab.) We drove across the country in February or March and my father parked the family with my grandfather and cousins in Cambridge for the remainder of the school year, while he went to work and looked for a house. I finished out 7th grade there.

I’ve often complained about the effects of moving so frequently, but there was a salubrious side to the occasional change of circumstances. If you grow up in one place your entire childhood, attending perhaps three different schools and living in the same location with the same groups of friends and acquaintances, the memories of those years, decades later, sorta run together. When you change homes every few years and schools even more often, you have a distinct set of memories for each. There are more different things to remember as an adult.

Cambridge was utterly unlike California in a way very different than Los Angeles was unlike Apple Valley. Everything was green; you didn’t have to water your lawn. The town was small, population about 2000 (and it still is, decades later), and if everyone didn’t know each other, everyone knew of each other. It was maybe a square mile, surrounded in every direction by farmland snaked through by two-lane highways. The air smelled different than it had in California. It would be humid in the summer, and it snowed in the winter. There were fireflies and thunderstorms. There were three or four churches, all Christian (Methodist, Baptist, Lutheran). There was one market, Wayne’s Super Value, where my Uncle Stanley (husband of my father’s sister, my Aunt Betty) worked as the butcher. There was a general store called Swan’s across the street, that had an old-fashioned soda-fountain counter. Both had paperback racks where I bought many of my early books; Swan’s also had plastic models, of cars, ships, spaceships.

Cambridge was utterly unlike California in a way very different than Los Angeles was unlike Apple Valley. Everything was green; you didn’t have to water your lawn. The town was small, population about 2000 (and it still is, decades later), and if everyone didn’t know each other, everyone knew of each other. It was maybe a square mile, surrounded in every direction by farmland snaked through by two-lane highways. The air smelled different than it had in California. It would be humid in the summer, and it snowed in the winter. There were fireflies and thunderstorms. There were three or four churches, all Christian (Methodist, Baptist, Lutheran). There was one market, Wayne’s Super Value, where my Uncle Stanley (husband of my father’s sister, my Aunt Betty) worked as the butcher. There was a general store called Swan’s across the street, that had an old-fashioned soda-fountain counter. Both had paperback racks where I bought many of my early books; Swan’s also had plastic models, of cars, ships, spaceships.

Despite its small size (Kewanee, to the east, where my mother grew up, was six times larger), Cambridge was the seat of Henry County, meaning the county courthouse was there [pic]. There was a decent public library; I spent time there obsessed with paging through old National Geographic magazines (for some reason, I became obsessed with compiling names of US aircraft carriers—perhaps because those names reputedly inspired the naming of starships in Star Trek). My mother’s father had been sheriff there – this story is on my genealogy page, but I’ll repeat it here – which is why my mother’s family had moved to Cambridge, and so how my parents met. Byron Pierce, born 1900, sheriff of Henry County, was killed in 1946 in a shootout.

Byron was Sheriff of Henry County at the time of his death. He was shot and killed by a recent discharged from a mental hospital while investigating a problem at the killer’s farm. Details can still be found on a couple websites, including this Chicago Tribune front page [alas this link, http://archives.chicagotribune.com/1946/06/14/page/1/article/kills-brother-sheriff-seized-in-gun-battle, no longer works; perhaps it required paid access] from June 14, 1946, and this History of the Henry County Sheriff’s Office, http://www.henrycty.com/Departments/Sheriffs-Office/The-History.

That history was family lore as I grew up, and the details of which I only discovered recently.

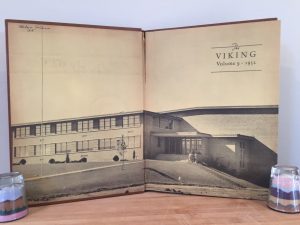

We landed in Cambridge and I attended the local junior high school – the same school where my parents had graduated in 1951 and 1952—to finish 7th grade. The classes were large enough that each year’s class was divided into two classrooms – basically, the smarter ones in one class, the others in the other. We had to memorize the recite the Gettysburg Address. The math teacher was the P.E. teacher. In P.E. a couple of weeks was devoted to golf. The school wasn’t far from my grandfather’s house, where we lived (half a mile), but the school bus I had to take wound out around the farmlands, to pick up one or two kids from each of widely scattered farmhouses, and so amounted to at least a half hour ride, or perhaps 45 minutes, in the morning and again the afternoon.

We landed in Cambridge and I attended the local junior high school – the same school where my parents had graduated in 1951 and 1952—to finish 7th grade. The classes were large enough that each year’s class was divided into two classrooms – basically, the smarter ones in one class, the others in the other. We had to memorize the recite the Gettysburg Address. The math teacher was the P.E. teacher. In P.E. a couple of weeks was devoted to golf. The school wasn’t far from my grandfather’s house, where we lived (half a mile), but the school bus I had to take wound out around the farmlands, to pick up one or two kids from each of widely scattered farmhouses, and so amounted to at least a half hour ride, or perhaps 45 minutes, in the morning and again the afternoon.

I took to the social strain of changing schools so often less and less well. For the first half of seventh grade in Reseda, I took a music class, to learn to play an instrument. I was obliged (by my father) to learn clarinet, because that’s what he had played. (I had been inclined toward a flute, but no I was told that’s for girls.) I did fairly well, in those first few months; one of the top two or three students, as I’d routinely been in all classes. Then we moved to Cambridge, which had different musical instruction protocols, there was no place to put me but in the “band” where all the students already had a year or more of instruction and practice. I was dismal compared to them, and I never caught up. Later, in Glen Ellyn, I enrolled in band again, and did no better than to sit among the third clarinets. In high school there, I was reassigned to play a contra-base clarinet – an instrument shaped like huge saxophone, but black like a clarinet – and did OK. Most band scores had no part specifically for a contra-base clarinet, so I was given the tuba part, and had to adjust the key. Again I did OK, and I even performed a solo line in a piece during one of the evening concerts the band performed for parents. At the same time, I had my father’s regular clarinet, and when the band served as a marching band, as at the annual homecoming parades, I played that.

(Without going into detail, this same effect happened a couple times during my professional career at Rocketdyne. Starting from scratch, I was top of class. Coming in late, I never caught up.)

In the 1960s a railroad ran through Cambridge, diagonally, and passed behind my grandfather’s house where we lived by only 100 feet. Freight trains went by in the middle of the night, and the whole house rumbled. The railroad has long since been decommissioned and its grounds grown over, but you can see its diagonal path in the satellite view of modern Cambridge. A few years after we lived there, when I discovered the novels and stories of Ray Bradbury, I recognized and identified his fictional “Green Town” with Cambridge. Bradbury had grown up in in Waukegan, actually, a relatively large town in the far northeast corner of Illinois, but his descriptions of his Green Town were perfectly illustrated by my memories of Cambridge.

Summer 1968: Illinois — Glen Ellyn

My father had gotten a job working at what became Fermilab, in Batavia, a suburb some 15 or 20 miles west of downtown Chicago. He found a house in Glen Ellyn, closer in to the city. The house was in a development (i.e. many streets of similar houses built to similar floor plans, all built about 1961), an area that was an odd blend of Los Angeles suburban tracts and open Illinois countryside. It was at 22W612 Arbor Lane (the W for ‘west’), across a highway with a view of the Morton Arboretum (https://www.mortonarb.org/), a large private nature preserve. We moved in there over the summer of 1968. It was a split-level house.  (The photo is a current Google Maps Street View screen capture. The trees are far larger now than they were in 1968.) The right half was at ground level; the left half was two stories, with the bottom half sunk half a floor into the ground. From the main floor living room, you either walked half a flight of steps up, to the top floor bedrooms (my parents, my sisters, and Kevin), or half a flight of steps down, to a family room, a combination laundry room bathroom, and another bedroom. I was given the private downstairs bedroom, which had its own exit, via an outside sunken stairwell.

(The photo is a current Google Maps Street View screen capture. The trees are far larger now than they were in 1968.) The right half was at ground level; the left half was two stories, with the bottom half sunk half a floor into the ground. From the main floor living room, you either walked half a flight of steps up, to the top floor bedrooms (my parents, my sisters, and Kevin), or half a flight of steps down, to a family room, a combination laundry room bathroom, and another bedroom. I was given the private downstairs bedroom, which had its own exit, via an outside sunken stairwell.

One startling aspect of home properties in this area is that there were no fences between properties, not even around the back yards. There might be shrubs or trees marking boundaries (we had some raspberry bushes at the back boundary of our back yard, and a willow tree in the left back corner), but there was nothing to prevent you from walking into your neighbors’ yards and peering in their back windows. In Southern California, there were walls surrounding every property, so that you had some reasonable expectation of privacy in your back yard.

A consequence of this was that our Samoyed, Tina, when let out into the back yard, had to be kept on a leash, or as we typically did, hooked to a chain, maybe 30 feet long, that was anchored to a post in the middle of the yard.

I attended 8th grade at Glencrest Junior High School, about a 2-mile bus ride north, just off Route 53.

In early 1969 I had a ruptured appendix and spent two weeks in the hospital. (My parents were for some reason skeptical of visiting doctors or dentists, but when I had this excruciating pain in my lower right belly one night and could not stand up straight, I was taken to a doctor, who immediately put me to the hospital. I had peritonitis, I had an operation, and my impression was that I was lucky to have survived. A hundred years earlier, I would not have. Thanks modern medicine.) I know exactly when it was, because I watched the Trek episode “The Cloud Minders,” first broadcast 28 Feb 1969, from that hospital room. My father sneered at it. That’s science fiction? Floating cities?

At that junior high I had an English teacher who would not award a grade above C without extra credit, i.e., submitted extra essays beyond what was required. She doubled as my “homeroom” teacher, and this is where book carts were brought in periodically with paperbacks for sale. This is when I discovered Ray Bradbury. (Also around this time I discovered actual bookstores in nearby malls. See my “15 Ways to Buy a Book” essay.)

And I had a science class led by a young teacher with the unfortunate name of Mr. Schnuckel. Of course kids made fun of him, for his odd name. And he almost broke down and cried one time, in class, after some hazing.

And I had a harasser, for the only time in my life, fortunately – being a bit of a nerd, and a not obviously straight boy. His name was Grant Hedmark. He teased me at my locker. And one day when I’d come back from a sick day, he told me I didn’t have to report to the principal. We were sitting in the gym. I was subsequently called into the principal’s office – for the only time ever in my entire life – and disciplined for not having checked in. Grant Hedmark kidded me for not knowing what a “box” was. He was a screwball.

1968-1969: Boy Scouts in Illinois

Once we settled in Glen Ellyn my father looked up the nearest Boy Scout Troop, which met at Arbor View Elementary School, about half a mile away, close enough to walk. I don’t remember the Troop number. It wasn’t as serious a group as the one in Reseda. The weekly meetings were short and devolved into informal basketball games in the gym where we met. My interests had been expanding toward books, and later reruns of Star Trek when it went into syndication (meaning reruns were shown five nights a week) in the Fall of 1969. I was a member of the troop for a year or so, but I dropped pursuit of further merit badges, or toward the next rank of Life. There were camp outs, of which I only remember a couple. One involved a 20-mile hike, all on one day, carrying full backpacks. It was a training hike for some of the older scouts who would a week-long hike later in the year. I distinctly remember, after finishing the hike and taking off my backpack, the feeling was like floating in the air. Another event was a one-day competition of some sort (there had been one with the LA troop also) on a day that was clear and sunny but cold. By the end of the day my feet were numb.

1969-1971: High School in Illinois

In the Fall of 1969 I entered 9th grade at Glenbard East High School (https://www.glenbardeasths.org/) , in the neighboring town of Lombard (thus the name). There was also a Glenbard West, and later a North and a South. It was a longer bus ride away; 4 or 5 miles. This school was built like an L- or T-shaped three story office building, which is to say, a single structure that you could stay in for school all day, whatever the weather. (Schools in California were built as bungalows or separate rows of classrooms connected by covered walkways, in the event of rain.) I took the standard English class, the standard math classes (trig, geometry, I think), an intro science class followed by a chemistry class in 10th grade, and two years of beginning German. I enrolled in band and played that contra-base clarinet, and the regular clarinet the two or three times a year the band marches or played at basketball games. I took a “speech” course about standing in front of the class to give persuasive speeches. I recall giving a speech about UFOs, just about the time I was realizing UFOs were not evidence of alien spacecraft but that something psychological was going on instead. The school had a quite large library, and I discovered books of both science fiction and science I had not seen before.

I don’t remember much about P.E. class – it was required of course – except that, given winter weather in that part of the country, P.E. was sometimes held in a basement room where the free weights were, and floor pads. The subject changed every two weeks. One subject was wrestling, on those floor mats. I hated P.E.

It was a large high school and had an auditorium for performances. The Theater Arts class put on a production of the famous musical “Oklahoma,” which my parents and I attended. My parents were very impressed.

In retrospect my most ignominious event at this high school was my participation in an annual science fair. High school science fairs are where students grow lima beans in glass jars with and without light, or with and without classical music, or whatnot. They’re clichés. I didn’t see the point. I feel like channeling Sheldon Cooper here—these things are known, what’s the point of replicating them? I understand. I can look them up. But I was obliged to participate. I was already too withdrawn a student to, you know, approach my teacher (chemistry by this time) for ideas. (More on how I became so withdrawn, below.) So my father suggested I do something related to the Batavia accelerator project. And the result was my building an architectural *model* of the proposed accelerator site with central office building built of cardboard. It was on a big piece of plywood, maybe 4×5 feet, using plaster of paris or whatever materials architects use to build such models. Without ever discussing this with my teacher at school, my father and I showed up on the day of the science fair and carried this thing inside. The fair starts; judges walk around to evaluate. They asked me questions – yes, I knew the difference between hydrogen and helium – but they didn’t my point in building a model rather than conducting some kind of experiment. I got a third-place ribbon, just one better than “participated.”

1971-1973: High School in California

We moved back to California in the summer of 1971. It may have been that the Batavia project was done. It may have been that since his mother had died, my father didn’t feel compelled to stay in Illinois. And it was partly because my parents just liked California more than Illinois. In any event, it was a staged move like the previous one. My father went back to work in LA (he stayed with my Uncle in Sepulveda for those weeks) while my mother and us kids stayed in Apple Valley with my grandmother. Also, we’d acquired a second car in Illinois—a used 1964 Buick Skylark—which my grandfather drove to California for us.

Having two cars for the cross-country drive made it plausible to take some stuff in the cars, knowing we would be laid over in Apple Valley for several weeks, that otherwise would have been packed and shipped by the movers. Primary for me was my telescope, which I disassembled and put back into the rectangular box in came in. Being in the desert for weeks would provide prime opportunities for clear sky viewing. My ulterior motive was to take a bunch of my books that I’d collected—all paperbacks, at this point—to read over those same weeks. I managed to fit a couple of dozen paperbacks in the niches between parts of the telescope in that box. Since 1970 I had kept a log of books I’d read, and once we arrived in California I began a similar log for every book and magazine I purchased, and from these I can be fairly precise about when we arrived in California (by June 25th) and when we moved into the house in Sepulveda (August 10th). (I’ve kept these logs ever since, of course, migrating from lists on lined notebook paper, to bound ledgers, to MS Access databases.)

We moved into a house in an area of the San Fernando Valley then called Sepulveda, later called North Hills. By coincidence, the house my parents decided on was on Hayvenhurst Avenue, just one block south of where my Uncle Bob had lived for years. Hayvenhurst was a busy secondary street, two lanes in each direction north and south, so it didn’t provide the privacy of our previous houses on quiet residential streets. Rather like the Reseda house, it was smallish, with four bedrooms and two baths, in 1366 square feet (via Zillow). It had a pool in the backyard, and a freestanding garage at the back corner of the property letting out onto an alley that was rarely used; our cars would be parked on the curb in front of the house. My brother and I had the two front bedrooms facing the street; Sue and Lisa shared a bedroom looking into the back yard; my parents had the larger back corner bedroom. At some point they acquired a waterbed, which were popular at the time. Our dog Tina had the run of the enclosed backyard without having to be chained, as she had been in Illinois and Apple Valley. During the years we lived there we acquired a second dog, a Shelty, named Sam (for Sir Anthony Madison; another purebred). He tended to attach himself to me, and slept in my bedroom by the closed bedroom door at night.

I attended James Monroe High School, a mile walk from home; back in California, I was back to walking to school and not having to take a bus. (I assume my siblings also walked to their schools, but I wasn’t really paying attention.) Like most LA schools of the time, it consisted of numerous disconnected buildings linked by at most covered walkways. Though I had done well in high school in Illinois, the California school did not quite trust my good grades from there, and so I was put in some good classes but not the full range of academic courses I might have taken in Illinois. I had math, and English, and some modular history course (the trend then was to abandon teaching traditional American history courses and to focus on particular topics for ten weeks at a time, e.g. the Civil War). But no science course. I’d taken Physical Science and Chemistry in Illinois, and the next logical class would be biology. But I got no biology course in California high school, though I did get in to physics in the 12th grade.

Denied a full range of academic classes for my 11th grade, I had some options, and one option I chose was typing, which in retrospect was as valuable a course as any of the others. I became proficient very quickly. Around the same time, in late 1971, my family acquired a small, portable typewriter – which I still have. And for whatever reason, when my mother didn’t need it to write a business letter, or somesuch, it stayed in my bedroom on that half-desk my father had built. And so I began….typing exercises. Free-form fantasias at first, spoofs of foreign languages whose words had too many letters for their syllables, allusions to current events, and after a time, a more conventional journal, or diary, and place for me to type lists. All this typing went on to the same three-punch holed lined paper we wrote our essays on for school. Unknowingly defiant of standard manuscript practices (since they weren’t manuscripts intended for submitting anywhere), they were typed single-spaced on both sides of each piece of paper. And then gathered into folders, with metal binding straps, at the end of each year. I wrote these through the 1970s, some years at great length; they continued, slackening a bit, into the 1980s, until the end of that decade when I acquired a computer and any such writing I wanted to do became electronic, not typed. Some years of this journal were hundreds of pages long; the aggregate total must be two or three thousand (single-spaced typed) pages. I still have them all, of course, and from this point – late 1971—am consulting some of them on details of this time. (Like, I hadn’t recalled that my grandfather drove our Buick Skylark to California for us, until I read about it in a recollection in my 1979 journal.)

So in 11th grade I took the courses I was given. I had already become withdrawn and unambitious, though I did well in the classes I took. As at every previous school, I became friends with one or two other boys – Philip Klutch was the principal one here – but never had an opportunity to hang out with them outside of school. Philip lived in the other direction. I walked home each day from school, went into my bedroom and closed the door against cigarette smoke and TV noise, did my homework, wrote my typed journal, read my books.

There was some scholastic society that all the top students joined. I didn’t. The key event in the 11th grade is that at some point I noticed, perhaps on a poster in the hallway or in the library, that something called the PSAT (for Preliminary Scholastic Aptitude Test) was strongly suggested for any students planning to go to college. No one at school had told me about it; my parents knew nothing about it. But I signed up. I took the test, and became one of the four top scorers at my high school. This was a big deal. The local newspaper, the Valley Greensheet, published a front page with all the top scorers from high schools in the San Fernando Valley. There I am. I still have the paper [pic].

This attracted the attention of the high school college counselor, Mr. (Eugene) Friedman, who also taught the 12th grade AP (advanced placement) English class. I was called out of class one day in the 11th grade to meet him, once he’d seen the PSAT scores. He arranged to get me into all AP classes in the 12th grade, including his, and got me out of P.E. to serve as his assistant for that period in his counselor’s office. Sometimes I graded his papers from his other classes. Mr. Friedman encouraged me to apply for the very top scientific schools in the country – Caltech! MIT! – with the more local UCLA as a backup.

12th grade came, and I took all these classes and did pretty well. I applied to MIT, which entailed visiting an MIT alumnus who lived in a very fancy apartment in the area between Westwood and Beverly Hills, and got on the waiting list. I applied to CalTech, which entailed interviewing with two CalTech representatives who came to our high school to interview me and two other boys who had applied. One of them got it; I didn’t. So I went to UCLA.

1973-1977: UCLA

This will be the last section about my childhood and early adulthood in this post, because after UCLA the family moved away and I lived alone, so that’s a different chapter of my life.

If I recall correctly in this era there were California sponsored scholarships for college attendance. My family would have qualified had I been accepted to CalTech or MIT – which would have required moving away from home and living in a dorm. (CalTech was conceivably within driving distance, but freshmen there were required to live on campus.) Since I went to UCLA, and my family didn’t qualify for any kind of scholarship. And while the idea of living on or near campus was debatable, it was out of the question for financial reasons. And so I lived at home, and commuted, often in rush-hour traffic, the 15 miles to UCLA and back.

As it happened my best friend in high school, Philip Klutch, also ended up on UCLA. And so we car-pooled the entire four years. (For part of that time one or two of Phil’s friends joined the carpool.) I was given to drive our family’s second car, that 1964 Buick Skylark with peeling paint on the hood. (So my mother had to do her grocery shopping on days I didn’t drive.) Phil drove his family’s car, and early ‘60s Plymouth or Dodge with push-buttons on the dashboard to shift gears. Phil lived in Panorama City, about 5 miles away, in a rather shabby third floor apartment with his parents. (How did he get to high school? He can’t have walked. Were there buses? I don’t recall.) His father was a mailman. Phil had grand ambitions to study physics, and majored in physics at UCLA, and did OK. He went to grad school at UC Irvine, in the ‘80s, then spent most of his career teaching at community colleges. He got married and became extremely religious in the orthodox faith of his parents, having three kids with Biblical names. We got in touch about 10 years ago – his wife somehow found me on the internet – and we met for coffee. He passed on my invitation to dinner, because my kitchen was not kosher. (This seems to be him right here: https://www.linkedin.com/in/philipklutch. He’s still alive!)

At some point during our years of commuting, Phil, or his parents, realized that for him to come pick me up was a longer drive for him than for me to pick him up and then drive to UCLA. He wanted to adjust the schedule to equalize the mileage. My mother scowled and say, of course, he’s a Jew.

I liked UCLA. I liked the campus, its landscape and many varied buildings (the four on the “quad” in traditional style like the buildings at Harvard, say, many others more contemporary glass towers), its large bookstore, its two enormous libraries. I initially majored in astronomy, because that was my childhood passion. For the first two undergrad years, your major doesn’t matter much; you take basic science courses, a certain number of “breadth” courses (in subjects outside your major), and so on. Of course for astronomy, those basic science courses are physics, and math. I made an error in presuming my AP math course in high school would replace the first two quarters of calculus. (UCLA runs on a quarter, not semester, system, with three quarters per year plus an optional summer session.) I began with third quarter Calculus and was lost. It was about parametric equations, but my early calculus education wasn’t strong enough to understand that subject well. I should have started college Calculus courses from the beginning.

At the same time, I took various breadth courses, like an intro to psychology. Which in that (benighted) era, consisted of reading Freud (who has since largely been discredited and dismissed). Such intro courses were held in large auditoriums with a two or three hundred students watching the professor lecture from the stage, three times a week. Once a week there would be an extra session with a teaching assistant, a smaller gathering (there must have been several of them for the entire class) to discuss homework and take questions.

I was OK in physics, for the first year and a half or so. My breaking point came in the last quarter of my sophomore year, which was about quantum mechanics, in particular Feynman diagrams. I did not get it. I lost my intuition. I got a C, or maybe a D (I can look this up).

And so I switch my major to math, because I had done better on average in math courses, despite that initial trouble, than the physics courses. At this point in my academic career, I had no clear idea of a career path; I just needed to finish my undergraduate degree.

A major way college is different than high school is that at college you aren’t are busy every hour for two thirds of the day. Typically at UCLA I would enroll in three or four classes per quarter. As described each course typically consisted of three lecture sessions and one T.A. session per week, four hours total, so in a 10 week quarter you would be in class 40 hours, and earn 4 units. Some classes omitted the TA session and were worth 3 units. A minimal load each quarter was 12 units; 16 pushing it; usually the balance was in the middle with a mix of classes. So you were in a classroom 12 or 15 hours a week. Depending on the actual schedule of your classes, you might not need to be on campus until 10 or 11 in the morning, some days. Since I was carpooling with Phil, we both had to be there for the extent of our combined schedules. (We were in virtually no classes together, as I recall, which was odd because he was a physics major.)

So I was on campus many hours when I wasn’t in class. I usually hung out in one of the two big libraries. The Powell library was the original library on campus, a stately brick structure of several stories and wide high-ceilinged hallways. In the center of the three-sided brick structure were the “stacks,” three or four low-ceilinged floors of metal shelving and walkways, whose ambience was like being inside a submarine. I didn’t realize it at the time, but this structure was temporary; years later when I returned, this structure was gone and the brick building had been expanded with large rooms and traditional wooden shelving for all those books. The stacks when I was there had numerous little cubby-holes with study desks, and finding one of those isolated you from the campus crowds as well as you would want.

The other library, the Research Library at the north end of campus, was a modern 1960s era (I’m guessing) four or five story building with few places to study and mostly row upon row of books. As many libraries do, the Research Library had several shelves of new arrival on the main floor near the checkout desk, and I would always browse those, and discovered numerous authors and works I hadn’t encountered before (Italo Calvino comes to mind).

The Research Library had a basement, and down there was a Theater Arts library, which had thousands of plays and movie and TV scripts. I was able to check out several Star Trek and Mission: Impossible scripts (the library only had a few of each, not a full run of all episodes), and discovered that my conception of the format of a TV script was entirely wrong.

Over the four years I took my regimen of physics and math courses, just one astronomy course before I changed majors, and a bunch of optional courses, some in the sciences and some in other subjects as already mentioned. I took a geology course; a linguistics course; that psychology course I mentioned. I took several quarters of beginning German (with Frau Hielscher, heel-sher), which were easy because I didn’t presume on my earlier high school courses and instead started from scratch. I took one quarter of Russian, because I had registered late that quarter and it was one of the few courses still open. I learned little of the language, but gained an appreciation for how different a language could be from English or German or French. (To say nothing of Chinese and Bantu or the thousands of other languages I’ve never looked at.) There are no articles in Russian; there is no “a chair” or “the chair,” only “chair.”

I took a history of music course, and audited a second one, because I was fascinated by the subject and had never learned anything about it, at home or in high school band. (In high school band they hand out pieces to learn and perhaps play at concerts, without any context about the composers or when the music was written. Actually high school English classes were much the same; you read this classic novel, or Shakespeare play, and explore its meaning, without learning anything about the history of literature, why certain forms were popular in different eras, how even the idea of what a story should be changed over the centuries.) For the music course we were obliged to visit the “music lab,” in a wing of the Powell library, where you would check out a record – a literal LP record – to sit in a booth and listen to the record with headphones on. There was no other way to hear music individually, way back then. (Old movies and TV sometimes depict “listening booths,” like telephone booths, in corners of record stores, where you could sample a record before you bought it. Same idea.)

I was quite affected by the music courses. I learned all about the Bachs, the baroque era, classical music, the romantics, Mahler. The instructor’s favorite two pieces of music ever were Bach’s Saint Matthew Passion and his Mass in B Minor. Even then I realized that historically, up to a point in both music and art, everything was about religion, because they didn’t know about anything else, there was no popular or classical culture to draw inspiration from. In the second course when he got to Mahler, the instructor played sections of Mahler’s 4th, chosen since it’s the relatively shortest and cheeriest of his symphonies.

(But I learned about later composers, Shostakovich, Schoenberg, et al, on my own, by listening to the local classical music station. And I checked out a couple big books on classical music and famous symphonies from the public library, and paged through them.)

I never did take a biology course, not in high school or college! So I’m dim on the mechanics of cells, for example, though in subsequent years I became fascinated by evolution, especially the process of evolution—in part because it appeals to the grand sense of time that astrophysics, and science fiction, explore, and read a number of books, and articles in general science magazines, about that subject. And in part because, once you understand its mechanisms, you see that it’s inevitable, it can’t not happen, which makes it all the more peculiar that it is rejected by so many on religious or psychological grounds.

Even in mathematics I hit a conceptual barrier. This was a subject, I think in junior year, called simply “analysis.” It was about infinitesimals, curves drawn to asymptotes, and the idea was to justify and reinvent calculus from first principles. (In high school or freshman calculus, you get some very high level theory and then lots of rules for solving particular kinds of equations.) I didn’t do well. But in math, as in physics or any other general study, you can specialize or choose a particular area of study. So I gravitated toward classes in number theory, in group theory, in linear algebra—subjects that dealt with discrete objects and values and their relations. I did better in those classes.

You start freshman year in those big auditoriums with hundreds of students, even for the intro classes to your own major. By senior year, as you become increasingly specialized, you sit in ordinary classrooms with 10 or 11 other students.

I did OK in all these later classes, but the entire time I was in college, I did just enough to get by. I had no passion for any of these subjects, no career goal I was driving toward. I graduated UCLA with a solid B average.

It’s worth mentioning that in those days, at a state university attended by a state resident, the tuition per quarter was something like $210. Two hundred and ten dollars. Textbooks were relatively expensive even then. At a time a hardcover novel cost $7.95, a textbook would easily run $25 or $30, so a full quarter’s textbooks could approach $100. At the same time UCLA offered a textbook buy-back program, so – as long as the same text was being used in the following quarter – you could sell you text back to the UCLA Bookstore for a portion of the cost. I still have a dozen or so of my college texts; either the selections changed and I couldn’t sell them back, or I simply wanted to keep them.

I took courses over a couple summers, in part because my parents were anxious for me to finish college in just four years. It’s common now I gather, but even decades ago it wasn’t unusual to students to take four and half or five years to finish their bachelor’s degree. So one summer I took a course in the history of infectious diseases, at UCLA (reading Roueche’s Eleven Blue Men and Camus’ The Plague).

And another summer a took a basic English course at a community college (Valley College in North Hollywood). There are two interesting aspects to this story. First, it was required of all UCLA freshmen to take an entry-level English composition course, no matter your high school record. So I dutifully enrolled in English 1A. In the first week we wrote an essay in class and I got mine back scrawled in red ink with a grade of C minus, or something. I was shocked. Had I done just fine in AP English in the 12th grade? Looking at supposed errors in my paper, they struck me as extremely picky, as if the instructor had taken it upon himself to put the students in their place and convince them they needed his help to get their writing in shape.

I dropped the course and enrolled in the equivalent course at the community college, which was a perfectly allowable thing to do, the next Summer, of 1974. I remember only one aspect of the course: the textbook we were given to read, Logic and Contemporary Rhetoric, by Howard Kahane. It had a profound effect on my thinking, and my approach to the world. It wasn’t about being picky or cynical, but about understanding how the world works, especially in politics and advertising. A few years ago I wrote a post here about this book called The One Book I’d Have Every College Student Read. Somehow I earned 4.5 credits for the course, so I must have gotten at A+.