Sloman, Steven, & Fernbach, Philip. 2017. The Knowledge Illusion: Why We Never Think Alone. Riverhead. *** 1/2

Sloman, Steven, & Fernbach, Philip. 2017. The Knowledge Illusion: Why We Never Think Alone. Riverhead. *** 1/2

We live in a complex world, no one can know everything, and we depend on the knowledge of others. (I recall that Heinlein quote decrying specialists; he was wrong.) The three big themes here are ignorance, the illusion of understanding, and the community of knowledge. People overestimate how much they know, and we don’t actually remember much detail because the brain didn’t evolve to retain information; that information is mostly out there in the world itself, easily retrievable. We think in terms of cause and effect, but our naïve understanding of physics doesn’t correspond to reality. Hunting was a communal exercise, and in the modern world too we rely on experts to build everything around us. Technology extends thought by expanding knowledge held in the world. Opposition to science comes from lack of understanding, and also social pressures that inhibit people from changing their minds when new information comes available. In politics, the less informed people are, the stronger their opinions; they resort to ‘sacred values’ to avoid thinking about practical consequences. Being smart isn’t about IQ, but more about the degree one contributes to group success; it also involves activities, trust in the institutions and principles of science. Yet most people don’t want too much information; they prefer to rely on community beliefs of how things work. There will always be ignorance, and illusions; the latter may be necessary for the development of human civilization. Intelligence resides in the community, and our society has come far because most people cooperate most of the time. (post) (Read Feb 2025)

Nichols, Tom. 2021. Our Own Worst Enemy: The Assault from Within on Modern Democracy. Oxford. *** 1/2

Nichols, Tom. 2021. Our Own Worst Enemy: The Assault from Within on Modern Democracy. Oxford. *** 1/2

Nichols’ counter-intuitive thesis is that, despite what “everybody says,” these are not the worst times ever, rather in many ways we’ve never had it so good. So what’s the problem? We’re losing because we won; despite our success people *feel* miserable because they give in to their base instincts. [[ I would characterize this as human nature refined in an ancestral environment that is ill-at-ease in the modern one. ]] He explores these ideas along three lines: peace, affluence, and technological progress. He contrasts a small Italian village in which everyone mistrusts one another with the civil responsibilities required by those in a democracy. Americans have become overgrown children, angry at things they don’t understand and bad at assessing risk. Many see flaws in the system as something that justifies throwing the entire system out. Globalization has not ruined everything; that feeling arises from short memories, from rising expectations, immediate gratification, and little accountability. And our hyper-connected world allows crackpot ideas to spread, undermining the patience and perspective that liberal democracy required. Recommendations: people should become better citizens, e.g. read a reputable newspaper and turn off social media. Beware the reassurance of the pack and the safety of the herd; grapple with the ambiguities and consequences of freedom. He finishes by contemplating three nightmare scenarios and worries most about one in which insiders take control of the government because voters can’t produce coherent demands, life will go on, and people won’t care that elections are meaningless. (post) (Read Feb 2025)

Tyson, Neil deGrasse, & Walker, Lindsey Nyx. 2023. To Infinity and Beyond: A Journey of Cosmic Discovery. National Geographic. ** 1/2

Tyson, Neil deGrasse, & Walker, Lindsey Nyx. 2023. To Infinity and Beyond: A Journey of Cosmic Discovery. National Geographic. ** 1/2

A history and tour of exploration beyond the Earth, from flying in the atmosphere, passing by the sun and the planets, layers of the atmosphere and when space begins, then the age and size of the universe and ideas of worldlines, time travel, hyperspace, black holes, and warp drives. Heavy, and heavily-illustrated, the book’s coauthor is a producer and writer at StarTalk, Tyson’s podcast. The book is a routine tour through familiar topics, but it includes one of Tyson’s hobby-horses, his attention to physics in movies and TV shows. In this book we get asides about the implausibilites (and occasionally plausibilities) in Ad Astra, Top Gun: Maverick, Mission to Mars, Intersteller, and many others. (post) (Read Feb 2025)

Dawkins, Richard. 2011. The Magic of Reality: How We Know What’s Really True. Free Press. *** 1/2

Dawkins, Richard. 2011. The Magic of Reality: How We Know What’s Really True. Free Press. *** 1/2

With many illustrations by Dave McKean, this is a book, suitable for young adult readers, with three essential ideas: that *how* we know something is as interesting as what we know; that there have always been myths about what people have imagined to be true; and that reality is more interesting, more magical in a poetic sense, than all those myths. After an opening chapter about what reality is and what magic is, there are nine chapters on particular topics: the first person; different kinds of animals; what things are made of; why there are season; the sun; a rainbow; how everything began, whether we’re alone, and earthquakes. Almost every one of these chapters opens with a selection of myths from around the world that were intended to answer these question; the myths range from those of the Tasmanians to the Norse to the Hebrews. Two final chapters are more philosophical. Why do bad things happen? Because there is no natural justice; the universe doesn’t care what we want; everything does not happen for a reason. Finally, what is a miracle? Stories about turning water into wine, or Mohamed flying off on a winged horse, are due to rumor, coincidence, and snow-balling stories. Humans are programmed to see faces of other humans, and so we see them everywhere. Hume had a way to think about miracles: believe in them only if their falsehood would be even more miracles. There are many things science cannot explain, but that doesn’t mean that they won’t. Resorting to the supernatural is simply giving up, and not trying to understand. (post) (Read 2011; Feb 2025)

Kolbert, Elizabeth. 2024. H Is for Hope: Climate Change from A to Z. Ten Speed Press. ** 1/2

Kolbert, Elizabeth. 2024. H Is for Hope: Climate Change from A to Z. Ten Speed Press. ** 1/2

A book of 26 short essays, one for each letter of the alphabet, with illustrations by Wesley Allsbrook, covering climate change history and illues. Arrehnius was the Swedish scientist who constructed the first climate change model. There are visits with industries battling fossil fuel dependence, e.g. one making electric airplanes, another green concrete. Hope, Objections, Republicans, Xenophobia. Ending with a tour of Hoover Dam, where tour guides don’t want to talk about why the level of the water is so low. Despite the title, the author ends “Climate change isn’t a problem that can be solved by summoning the ‘will.’ It isn’t a problem that can be ‘fixed’ or ‘conquered,’ thought these words are often used. It isn’t going to have a happy ending, or a win-win ending, or, on a human timescale, any ending at all.” (post) (Read Jan 2025)

O’Connor, Cailin, & Weatherall, James Owen. 2018. The Misinformation Age: How False Beliefs Spread. Yale. ***

O’Connor, Cailin, & Weatherall, James Owen. 2018. The Misinformation Age: How False Beliefs Spread. Yale. ***

Not quite what I expected, but interesting nonetheless. A key point, already well-known, is that people form beliefs based on information from others, and acquiring false beliefs isn’t a matter of psychology or intelligence, but rather to various social factors. The running thread is how even scientists can form and perpetutate false beliefs, given the same social factors, and the way information passes from individual to individual and group to group. This is illustrated with social network diagrams (example shown). More than most people realize, these networks also go wrong when propagandists (typically for big business) work to undermind them, by manipulating evidence or selectively distributing it. The authors’ most provocative idea is a reimagining of democracy. The problem is that most people who vote have no idea what they are talking about; this is a “vulgar democracy.” What’s needed is an idea from Philip Kitcher: a “well-ordered science” to navigate between vulgar democracy and technocracy, in which decisions about issues of science are made by representative citizens able to understand and communcate those issues. This ideal situation may be utopian, and impractical, but it’s important at least “to abandon the notion of a popular vote as the proper way to adjudicate issues that require expert knowledge.” (post) (Read Jan 2025)

Lilla, Mark. 2024. Ignorance and Bliss: On Wanting Not to Know. Farrar, Straus and Giroux. ***

Lilla, Mark. 2024. Ignorance and Bliss: On Wanting Not to Know. Farrar, Straus and Giroux. ***

Framed by a parable of Plato’s cave, this is a philosophical consideration of the motivations for various flavors of ignorance: evasion, taboo, emptiness, innocence, and nostalgia. Evasion is about avoiding self-knowledge, including knowledge about the world, in favor of received false opinions in which people have an emotional stake. Taboos include prohibitions against acquiring knowledge about the world that would undermine faith. Emptiness is about uncertainty, which leads people to oracles and prophets, the more illiterate the better, with the history of Paul, who despised culture and preferred willful ignorance, and the many later prophets. Innocence is about the belief that newborns are blank slates, who moral purity must be protected until they are adults; thus the Hollywood cliché that children are wiser than adults, and thus Bowderization of books, gated communities, home schools. And nostalgia (the theme most pertinent to modern politicis) is about the longing for a simpler, happier world of the past, and the shedding of toxic knowledge about the world and themselves; and the flip idea that some nostalgiac people flee into the future, looking to an apocalypse or a rebirth. Nostalgia is a will to ignorance, a rejection of a present that is always found wanting. Lilla concludes by contrasting the openness to experience we like to think we possess, with the fact that many look away from the world, and retreat to the cave. (post) (Read Jan 2025)

Lakoff, George. 2008. The Political Mind: Why You Can’t Understand 21st-Century American Politics with an 18th-Century Brain. Viking. ***

Lakoff, George. 2008. The Political Mind: Why You Can’t Understand 21st-Century American Politics with an 18th-Century Brain. Viking. ***

Lakoff, a UC Berkeley prof, applies ideas familiar from the psychologists — principally that humans don’t think rationally, as many used to think — to make the point that Enlightenment ideas of reason are obsolete and untrue. He characterizes politics as being about conservatives and progressive, where he describes the former as being mostly concerned with obedience, responsibility, and discipline, and the letter as bieing driven by empathy to create a government whose responsibilities are protection and empowerment. These are useful take-aways, but there’s no evolutionary perspective here that might explain why these two styles of thinking came to exist, or how those Enlightenment ideas aren’t *wrong*, exactly, just idealistic and requiring conscious work. And there are flaws: he’s read Steven Pinker, but misunderstands and dismisses evolution; and he gets too bogged down in details of neurons and framing and so on. Still, worthy for the book’s strictly political perspectives. (post) (Read Jan 2025)

Adair, Bill. 2024. Beyond the Big Lie: The Epidemic of Political Lying, Why Republicans Do It More, and How It Could Burn Down Our Democracy. Atria Books. ***

Adair, Bill. 2024. Beyond the Big Lie: The Epidemic of Political Lying, Why Republicans Do It More, and How It Could Burn Down Our Democracy. Atria Books. ***

The founder of the PolitiFact describes varieties of lies, a “Lying Hall of Fame” (from Big Tobacco to Donald Trump), and how people fall for lies (e.g. that the 2020 election was stolen), with running accounts of several victims. Of key interest is how Adair, though he’d dissembled about it for fear of seeming biased, admits that (of course) Republicans lie more than Democrats, and other fact checkers observe the same thing. He consults various officials and journalists to speculate why this is so. Republicans want to win at all costs, without caring deeply about issues; Democrats are too wonky, too concerned about getting things right, while Republicans rely on pithy sound bites; and (as I’ve speculated myself) because Republicans see themselves in an epic struggle for the soul of America, and so a little lying isn’t so bad. With examples, some my own. Further: conservatives predictably claim PolitiFact is biased, without providing any examples of Democratic howlers that it missed. Finally: how can we stop the lying? Clearly fact-checking doesn’t have much impact. So: Ask the politicians. Keep score. Invite them to pledge not to lie. Track misinformation as data. (post) (Read Dec 2024)

Beauchamp, Zack. 2024. The Reactionary Spirit: How America’s Most Insidious Political Tradition Swept the World. PublicAffairs. ** 1/2

Beauchamp, Zack. 2024. The Reactionary Spirit: How America’s Most Insidious Political Tradition Swept the World. PublicAffairs. ** 1/2

Has democracy been a nice experiment that’s become unsustainable? Beauchamp considers democracy to be an upending of traditional hierarchies; the reactionary spirit is anti-democratic, seeking to restore those tribal hierarchies. (This basic division echoes ideas of several other writers covered here: Lakoff, Greene, Urban, Richardson.) He meets a CPAC attendee who unapologetically calls for the return of segregation. He talks with Milo Yiannopoulos. He examines several countries in detail, including Hungary, Israel, and India. He discusses Nietzsche, who attacked both democracy and Christianity. But at the end, the author is optimistic. This book is fine as a description of current events, but lacks any depth to try to explain *why* these things are happening (much less explore the evolutionary basis for these different political attitudes). (post) (Read Dec 2024)

Newitz, Annalee. 2024. Stories Are Weapons: Psychological Warfare and the American Mind. Norton. ***

Newitz, Annalee. 2024. Stories Are Weapons: Psychological Warfare and the American Mind. Norton. ***

This is about psychological warfare in the US, which means deliberately spinning the truth or telling alternative narratives for political purposes. It goes back long before social media, but came to the fore in advertising and wartime propaganda. A surprise of the book is that one of the key players in these “psyops” was one Paul Linebarger, now best known for his mid-century science fiction published under the pseudonym Cordwainer Smith. Other psyops included the mythmaking by the US government to encourage westward expansion, in the 18th and 18th centuries, and more recently how Steven Bannon, and then the Russians, targeted those with fascist tendencies with slogans like “drain the swamp” and “make America great again.” Culture war issues have included Charles Murray’s attempt to link IQ and economic fates, Joe McCarthy and Anita Bryant’s moral panic over homosexuals since the 1950s, and Fredric Wertham’s war against comics that anticipated today’s battles over “wokeness.” Finally there are ideas for disarmament. Rediscover actual history, with an example of a tribe in Oregon once declared to be extinct. Fight propaganda online, with suggestions for regulating social media. And how the public library is a metaphor for a rejuvenated public sphere. (post) (Read Dec 2024)

Haidt, Jonathan. 2024. The Anxious Generation: How the Great Rewiring of Childhood Is Causing an Epidemic of Mental Illness. Penguin. ***

Haidt, Jonathan. 2024. The Anxious Generation: How the Great Rewiring of Childhood Is Causing an Epidemic of Mental Illness. Penguin. ***

Expanding on a theme from Haidt & Lukianoff’s THE CODDLING OF THE AMERICAN MIND, Haidt here focuses on smartphones and social media and their deleterious effects. How is this worse than any past moral panics against new technology, from radio and TV and comic books and video games, and for that matter scrolls in ancient Greece? Well, he has data. There’s been a rise in teenage anxiety, depression, self-harming, and suicide among Gen Z beginning around 2010. He revisits the decline of play-based childhood, and the rise of phone-based childhood, how girls are more affected by social media than boys, and at the end has suggestions for “collective actions” for healthier childhoods: relax laws that over-protect children in the real world; schools should encourage more free play and recess. Parents should be gardeners, not carpenters. Delay introducing phones, instead find part-time jobs, tech-free camps, or take a gap year. I remain skeptical — it sounds like a variation of the conservative screed that life was better in the old days — but he does have data about actual harm. (post) (Read Dec 2024)

Hidalgo, Cesar. 2015. Why Information Grows: The Evolution of Order, from Atoms to Economies. Basic Books. ***

Hidalgo, Cesar. 2015. Why Information Grows: The Evolution of Order, from Atoms to Economies. Basic Books. ***

This book ties thematically with both Harari’s later NEXUS, in its concept of what information is, and Greene’s UNTIL THE END OF TIME, with the idea that information can grow just as order can despite the second law of thermodynamics, because both are temporary in the long run. The universe is made of energy, matter, and information, and the last grows by virtue of three facets of the universe: out-of-equilibrium systems (he recalls ideas from Ilya Prigogine; the obvious example is the Earth and Sun, which will remain out of equilibrium for billions of years, allowing life to evolve in Earth), the accumulation of information in solids (crystals; DNA), and the ability of matter to compute (how we can perform actions without “knowing” how to do them, an ability he calls “knowhow.”) Technically, information is measured by the number of bits needed to communicate an arrangement, so that, ironically, random sets of bits contain more information than well-ordered one. That’s a quarter of the book; the remainder explores ideas about how the growth of information drives economies, about social interactions and social networks, how large networks are a reflection of a society’s level of trust. (post) (Read Sep 2024)

Prothero, Stephen. 2016. Why Liberals Win the Culture Wars (Even When They Lose Elections): The Battles That Define America from Jefferson’s Heresies to Gay Marriage. HarperOne. ***

Prothero, Stephen. 2016. Why Liberals Win the Culture Wars (Even When They Lose Elections): The Battles That Define America from Jefferson’s Heresies to Gay Marriage. HarperOne. ***

Cultural wars in America are not new; they go back to Thomas Jefferson. The author’s thesis is 1) that conservatives start cultural wars, as inevitable societal change gradually passes them by; and 2) liberals win those wars as once-controversial topics (women’s suffrage, gay marriage) become cultural norms. Conservatives then find something else to complain about [as in 2024, transgender people]. I read just the introduction, which describes this culture wars cycle; the chapter on contemporary culture wars, essentially a history of social controversies since the 1960s, exacerbated by Reagan, Falwell, et al; and the conclusion, that despite a few isolated victories, conservatives lost the culture wars badly. Yet there will always be disagreements; there will always be gays and bigots. The deep unstated premise: there will always be change, and conservatives will always be uncomfortable with it. (Now in 2024, will Trump’s new regime change this conclusion? Trump may wreck swaths of the US government, but ultimately he will fail to change the culture.) (post) (Read Aug 2024)

Richardson, Heather Cox. 2023. Democracy Awakening: Notes on the State of America. Viking. ****

Richardson, Heather Cox. 2023. Democracy Awakening: Notes on the State of America. Viking. ****

Historian Richardson, now best known for her daily news commentaries at Letters from an American, looks back over the past century of American history to explain how we got to the point where someone like Trump could be elected president. Her style is straightforward and equanimous, matter-of-fact without being overly partisan, and she’s good at boiling down long histories and complex ideas into bite-sized chunks. Thus her definition of fascism: the idea that some people are better than others, and deserve to rule. A key historical thread is what she called the “liberal consensus” that emerged after World War II among both Democrats and Republicans: the idea that government was to regulate business, provide a basic social safety net, and invest in infrastructure. The first part of book is about conservative opposition to this, especially among racists in the south; the Ku Klux Klan; the glorification of the American cowboy; and intellectuals like William F. Buckley rejecting Enlightenment principles in favor of his religion. The second part is about the ascendance of Trump up to the “Big Lie” that the 2020 election was stolen from him. And the third part reviews principles of the Enlightenment, the founding of America, and considers what we can do to reclaim America from the authoritarians and autocrats. America is not based on land or religion or race, she emphasized, but on the concept of human equality. (post 1; post 2; post 3.) (Read Aug 2024)

Junger, Sebastian. 2021. Freedom. Simon & Schuster. *** 1/2

Junger, Sebastian. 2021. Freedom. Simon & Schuster. *** 1/2

Part memoir, part philosophical reflections, based on several sessions of walking, with a small group of friends, the railroad lines in Pennsylvania, living like hobos, avoiding security and police. Three themes. Freedom is being left alone and doing whatever you want, which is hard to do in a complex society where we are necessarily dependent on one another. (We don’t build our own houses, let alone refine our own gasoline.) Second, recalling the violence between the European immigrants who settled this area and the native Indians. The more free you were, the farther out from settlements, the greater the danger. Author describes how in disasters people are usually helpful toward each other, even sacrifice themselves for others. And how the largest of a group, whether individual male or army in a war, does not inevitably win. Three, how society has been able to think things through [to go beyond tribal morality in my terms] to establish higher principles. Democracy is an attempt to balance power and freedom. Beware leaders who aren’t willing to make sacrifices themselves, e.g. fight in battles alongside their men. With a discussion of social inequality and the “Gini coefficient”. Societies with high inequality dominate world history; how do individuals within them protect their freedoms? By thinking social values through, with examples of the Easter Rising revolution in Ireland, and a steel workers strike in Pittsburgh, winning by principle than by fighting. Finally, the author tires of wandering, and settles down, giving up a kind of freedom for a place to be at home. (post) (Read Jul 2024)

Coates, Ta-Nehisi. 2015. Between the World and Me. One World. *** 1/2

Coates, Ta-Nehisi. 2015. Between the World and Me. One World. *** 1/2

Memoir by a black intellectual written as a letter to his 15-year-old son on what he can expect as he grows up in America. Coates is deeply bitter but realistic about race relations in the US. Key phrases illuminate his perspective: about “how one should live within a black body” in a society where police are authorized to “destroy your body” even if only mistakenly. About “those Americans who believe they are white” when only a few decades before distinctions between, say, “Catholic, Corsican, Welsh, Mennonite, Jewish,” were very important. There are beautiful passages imagining a “specific slave woman” whose experiences of life are as complex as his son’s own; about the simplicity of seeing the race problem as black vs white; and finally, after visiting the mother of a childhood friend kill by police, reflecting on the “Dreamers” (those who aspire to the world the author cannot) whose technology is plundering the world. These final thoughts align the sins of racism with the hubris of progress that now threaten the safety of the planet. (post) (Read Jul 2024)

Westover, Tara. 2018. Educated: A Memoir. Random House. ***

Westover, Tara. 2018. Educated: A Memoir. Random House. ***

Memoir about the author growing up in rural Idaho, one of seven kids in a survivalist family who never sends their kids to doctors, or to school; who fear the government and are sure the Days of Abomination are due any moment. She’s determined to get out into the world, and she does so, and learns about all the things her parents never told her. Still, the title refers not so much to her secular education as it does coming to understand her family, and learn to understand them, if not entirely accept them. Interesting bits: Father reads from holy books but thinks most other books are harmful; when nothing happens at Y2K father, sure the world would end, feels betrayed by God; the family is extremely careless both in their junkyard business and in cross-country drives; in her studies at Cambridge Tara reflects on how history comes to be written. With reflections on my own family. (post) (Read Jul 2024)

Didion, Joan. 2005. The Year of Magical Thinking. Knopf. *** 1/2

Didion, Joan. 2005. The Year of Magical Thinking. Knopf. *** 1/2

Novelist and screenwriter Didion’s memoir about the sudden death of her husband John Gregory Dunne, in their apartment on New York’s upper east side, in Dec. 2003. The narrative follows details from ambulance trips to their daughter’s own hospital stays to learning how to live daily without his presence, in parallel with the gradual realization tht she is not thinking rationally, experiencing a kind of cognitive dissolance she comes to call “magical thinking.” She’s very matter of fact about the famous people they know, the exotic places they’ve lived, but also introspective in her speculations on how things might have gone otherwise, the role of luck in events, while being unable to completely avoid those magical habits of mind. As such it’s an example of struggling to reconcile the animistic thinking of base human nature with the conscious awareness needed to navigate modern society. (post) (Read Jul 2024)

Greene, Brian. 2020. Until the End of Time: Mind, Matter, and Our Search for Meaning in an Evolving Universe. Knopf. *****

Greene, Brian. 2020. Until the End of Time: Mind, Matter, and Our Search for Meaning in an Evolving Universe. Knopf. *****

A big picture book about the history of the cosmos, and humanity, with much familiar material but also two key themes of Greene’s own: the idea of nested stories to understand reality at various scales, and his idea of what kind of meaning we can deduce from our existence and the future of the universe. Early chapters concern entropy and evolution, and especially what the former actually means. Complexity including life, apparently contradicting the second law of thermodynamics, is possible because of what Greene calls the “entropic two-step,” essentially meaning the local complexity here will eventually drain back in the environment later. Then: the history since the big bang, “inflation” as the rare but inevitable consequence of repulsive gravity, the formation of the elements and of structures resulting in life. Darwinism at the molecular level. Life led to consciousness and the mind, and then to imagination, in particular to stories and why they are useful. Stories became religions with survival values and notions of the sacred. How beliefs arise, evolving to promote survival, not to understand reality. The roles of art in human society; artistic truth tells a higher-level story. The author fulfills the promise of the title by projecting the deep future: the fate of the sun and earth, black holes that sweep the galaxies clean. Thought might survive even the existence of matter, if it slows way down. Then the end of time and the disintegration of emptiness. Finally, meaning: There is no grand design or purpose; we exist while an infinite number of other possible people do not. Beyond that, perhaps our brains are not structured to answer the deep questions. We construct our own meaning. Perhaps, in the end, it is only story. (post 1; post 2; post 3; post 4; post 5) (Read Jul 2024)

Reich, Robert. 2018. The Common Good. Knopf. *** 1/2

Reich, Robert. 2018. The Common Good. Knopf. *** 1/2

A short book that lies at the intersection of politics, morality, and human nature, by the UC Berkeley economist. The “common good” is the set of shared values of a society, it’s not about socialism or political parties, and it’s a sense that’s been lost in recent years. How do we get it back? It was the basis for “we the people,” FDR’s four freedoms, civil rights, and public education. It’s the opposite of Martin Shkreli and Ayn Rand. (Reich however does not explore the deep evolutionary reasons why the common good came to exist, as other writers do.) Breakdowns in the shared understanding of a common good began in the 1960s, from Watergate to Iran-Contra to Newt Gingrich to Bernie Madoff and the financial crisis of 2008. Three broad structural breakdowns: whatever-it-takes-to-win politics; whatever-it-takes-to-maximize-profits; and whatever-it-takes-to-rig-the-economy. (Reich diplomatically does not mention that it’s Republicans and conservatives who do most of these things.) How to restore the common good? Bring back a sense of honor and shame. Hold people accountable. Identify and share the truth, rather than spreading lies and fake news. And revive civic education. And critical thinking, how to be skeptical but not cynical. Realize there are more good things happening in the world every day that we simply don’t hear about. (post) (Read Jun 2024)

Ahn, Woo-Kyoung. 2022. Thinking 101: How to Reason Better to Live Better. Flatiron. **

Ahn, Woo-Kyoung. 2022. Thinking 101: How to Reason Better to Live Better. Flatiron. **

Yet another book about cognitive biases, mixing psychology and self-help. The one distinction between this and similar books is that the author supplies suggestions for overcoming each of the eight biases she examines. These include the allure of fluency, confirmation bias, causal attribution, reliance on anecdotes, negativity bias, biased interpretation, perspective-taking, and delayed gratification. Bottom line: only learning to think better will lead to a better world. (post) (Read May 2024)

Gottschall, Jonathan. 2021. The Story Paradox: How Our Love of Storytelling Builds Societies and Tears Them Down. Basic Books. *** 1/2

Gottschall, Jonathan. 2021. The Story Paradox: How Our Love of Storytelling Builds Societies and Tears Them Down. Basic Books. *** 1/2

The paradox is that stories are necessary, but poisonous in some circumstances. The writer makes a host of key points, some familiar, some new to me. Storytellers rule the world, as used by totalitarian regimes including church dogmas, with the most contagious stories ever told being the gospels of Jesus. Conspiracies theories are actually conspiracy stories. Stories are about characters trying to resolve predicaments, and they have moral dimensions. They can evoke empathy for people different than the reader, but at the same time require a villain. We inherit our stories, as others inherit theirs (somewhat undermining the notion of essential evil). Narrative is reductionist, simplifying the world; we defend our stories to avoid loss of meaning. The escape from the rule of stories in the Dark Ages was by evidence that lifted us into the Enlightenement. But now we face one of the most successful storytellers in history: Big Blare [i.e. Trump]. Solutions? Don’t assault stories per se; find out which narratives about reality are true and which are false. And yet authoritarian system have been more common and stable over history that democracies. My own thoughts in the post conclude with the notion that perhaps both democracy and science are passing fades in human history, destined to give way inevitably to yet new authoritarian regimes (including Trump’s) and their “stories”; and how this spills over into the plausibility of traditional science fiction scenarios. (post) (Read May 2024)

Pinker, Steven. 2002. The Blank Slate: The Modern Denial of Human Nature. Viking. *****

Pinker, Steven. 2002. The Blank Slate: The Modern Denial of Human Nature. Viking. *****

Another big Pinker book summarizing and extending themes considered in his own earlier books and in books by Minsky, Wilson, Sagan/Druyan, Haidt, and Greene. The book actually addresses not one but three misapprehensions about the human mind: that it’s a “blank slate,” that there is such a thing as a “noble savage,” and that there is a “ghost in the machine,” i.e. a noncorporeal force, like a homunculus or a soul, riding in our brain and making our decisions for us. The first notion, with its implication that human nature is a product of education and environment, does not even bear close examination. Our instincts, and our ability to learn, indicate something already present in the mind (rather like firmware or the operating system in a computer) at birth. This understanding has replaced earlier ideas of associationalism and behaviorism of 20th century psychology, just as cognitive neuroscience and evolutionary psychology have undermined notions of the savage and the ghost. By page 101 Pinker closes his case that the mind is not a blank slate; the remainder of the book explains why the idea is resisted (fears of inequality, nihilism), and explores aspects of human nature: how we perceive reality, how our intuitions go wrong, why we suffer, our moral sensibilities. With special attention to politics, violence, gender, children, and the arts. Running themes include how these ideas challenge both liberal and conservative presumptions, and how the expansion of experience and knowledge over human history necessarily requires a transition from a monocultural morality to a multicultural one. Another vast book by Pinker that provides insight to virtually everything. The link here is to the 10th post summarizing the book, with links to the earlier nine. (post) (Read May 2024)

Greene, Joshua. 2013. Moral Tribes: Emotion, Reason, and the Gap Between Us and Them. Penguin. *****

Greene, Joshua. 2013. Moral Tribes: Emotion, Reason, and the Gap Between Us and Them. Penguin. *****

Keying off Garrett Hardin’s “tragedy of the commons,” the author explores the “tragedy of commonsense morality” to show the effects of different moral policies for sharing resources and dealing with conflicts. How did cooperation evolve at all, given Darwinian competition? Morality evolved to enable it, via altruism and unselfishness, as humans formed groups (tribes). But now humanity is in need for a “meta-morality” to avoid conflicts and solve problems among all tribes. Greene summarizes the roots of morality via the Prisoner’s Dilemma, tit for tat, Hobbes’ Leviathan, the trolley problem, etc. The solutions of this morality don’t always work in the modern world. His solution is a modified utilitarianism that he calls “deep pragmatism,” and shows how this approach can be applied, for example, to the abortion dispute. Finally, Greene defends liberalism and explains why he thinks liberal policites make the world happier. He quibbles a bit with implications of Haidt’s Moral Foundations Theory and claims that liberals’ moral tastes are more refined than those of conservatives; the latter have yet to outgrow the tribal morality that is unsuitable to the modern world. Thus liberal nations exhibit the highest levels of quality of life and happiness in the world. And he ends with six rules for modern “herders,” beginning with not trusting your moral instincts — “don’t believe everything you think” — how rights are invoked to end arguments when you have no evidence, how to focus on facts, be aware of our own biases, use common currency (e.g. science) for establishing facts, and giving. A big substantial book that ties together ideas about morality, evolution of the mind, politics, and psychological biases from many other writers (Pinker, Wilson, Haidt, Kahneman, and later reflected by Wallace and Gregg). A second post follows the link here. (post) (Read Apr 2024)

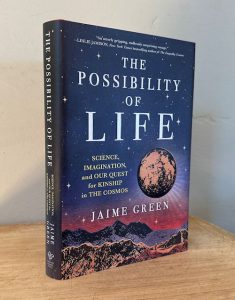

Green, Jaime. 2023. The Possibility of Life: Science, Imagination, and Our Quest for Kinship in the Cosmos. Hanover Square Press. ** 1/2

Green, Jaime. 2023. The Possibility of Life: Science, Imagination, and Our Quest for Kinship in the Cosmos. Hanover Square Press. ** 1/2

Thematically similar to Adam Frank’s LITTLE BOOK, focusing on the nature of life in the universe within the context of cosmic history, from the origin of life, the planets, of animals and people, and possible contact with other intelligent life. This book is replete with references to science fiction, mostly TV and movies but also some novels and even short stories, by authors from Le Guin to Baxter to Butler to Lem to Chiang to Mieville. Like Frank she considers biosignatures and SETI. She admits she’s not concerned with odds; life might indeed be extremely rare, but thinking about it is what matters. In passing, I noted her point that life on Earth is so various that animals in Australia, for example, might as well be aliens compared to the rest of the world. (post) (Read Mar 2024)

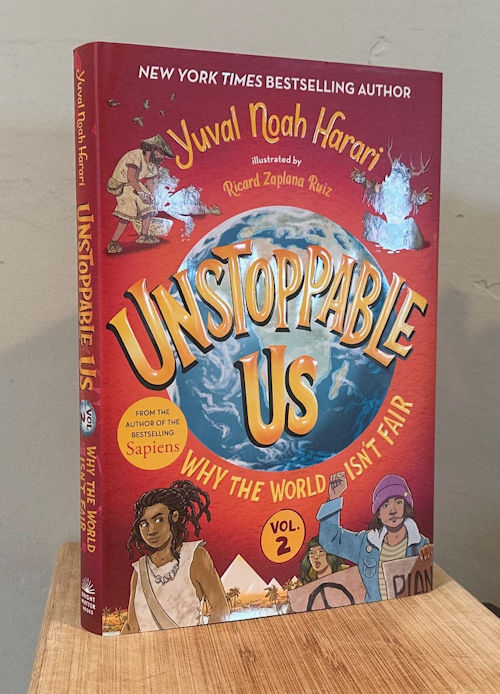

Harari, Yuval Noah. 2024. Unstoppable Us, Volume 2: Why the World Isn’t Fair. Bright Matter Books. *** 1/2

Harari, Yuval Noah. 2024. Unstoppable Us, Volume 2: Why the World Isn’t Fair. Bright Matter Books. *** 1/2

This second volume also has four chapters. First: the agricultural revolution, during which hunter-gatherers settled into villages and took control of other animals: goats, pigs, cows. The transition had problems: crops were subject to pests and droughts. Chiefs and priests explained how sacrifices were needed to appease the spirit gods, and if they didn’t work, you must have done something wrong. Second, how living as a farmer or herder is a lot more work than being a hunter/gatherer. As villages grew, diseases spread easily, people acquired more possessions, neighboring villages fought, and the peaceful became violent in order to survive. Farmers and gatherers learned to think differently. Third, larger communities led to more and more problems, including leaders to make decisions, taxes and assessors to determine them, punishments for non-payers, and slavery. This led to writing, and symbols for numbers, and eventually abstract works like poetry. The need to find documents that held this writing led to bureacracy, then schools, and exams. Fourth, how to get people to follow the rules. You invent stories. Priests tell stories about the gods who created the world and made its rules; follow the rules, heaven; disobey, you get eaten by a crocodile. Truth didn’t matter; believing in the stories and following the rules made society possible. In the world there are things we can sense, things only one person can feel, and things that are shared dreams. These last are harmful when they justify wars. But stories can change– e.g. about women, and gays. Part of growing up is learning which stories to keep, and which to change. Harari is remarkably blunt in describing things most historians take for granted, but which would offend true believers of all kinds. His take on changing stories synchs with how morality has evolved, as discussed by Pinker and Greene. (post) (Read Mar 2024)

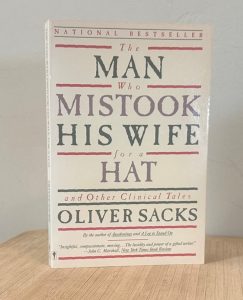

Sacks, Oliver. 1987. The Man Who Mistook His Wife for a Hat: and Other Clinical Tales. Perennial. *** 1/2

Sacks, Oliver. 1987. The Man Who Mistook His Wife for a Hat: and Other Clinical Tales. Perennial. *** 1/2

First published in 1985, this is a collection of essays by a clinical neurologist describing the effects of various kinds of neurological disorders. The gist is that these disorders are associated with specific parts of the brain; recourse to demons or souls had been abandoned by the 1960s and ’70s. The famous title essay is about a musician who has trouble recognizing faces, who sometimes perceives faces that aren’t there, and who, searching for his hat as he prepares to leave, grasps his wife’s head instead. Sacks doesn’t always diagnose; often he speculates on how people live with such disorders, even whether they might not be disadvantages or disabilities. Other cases include a man who’s lost his memory of everything after 1945; a medical student who experiences enhanced senses of color and smell but only for three days; Hildegard, whose migraines she saw as visions from God; twins in a mental hospital who can name the day of the week for any date, but who can’t do simple arithmetic; and an autistic man with no interest in the abstract, only the concrete. (This last came before the current understanding of the “spectrum” of autism.) Sacks concludes that the brain is both a machine and a computer, while our mental processes also involve judging and feeling, without which we are computer-like. (post) (Read Mar 2024)

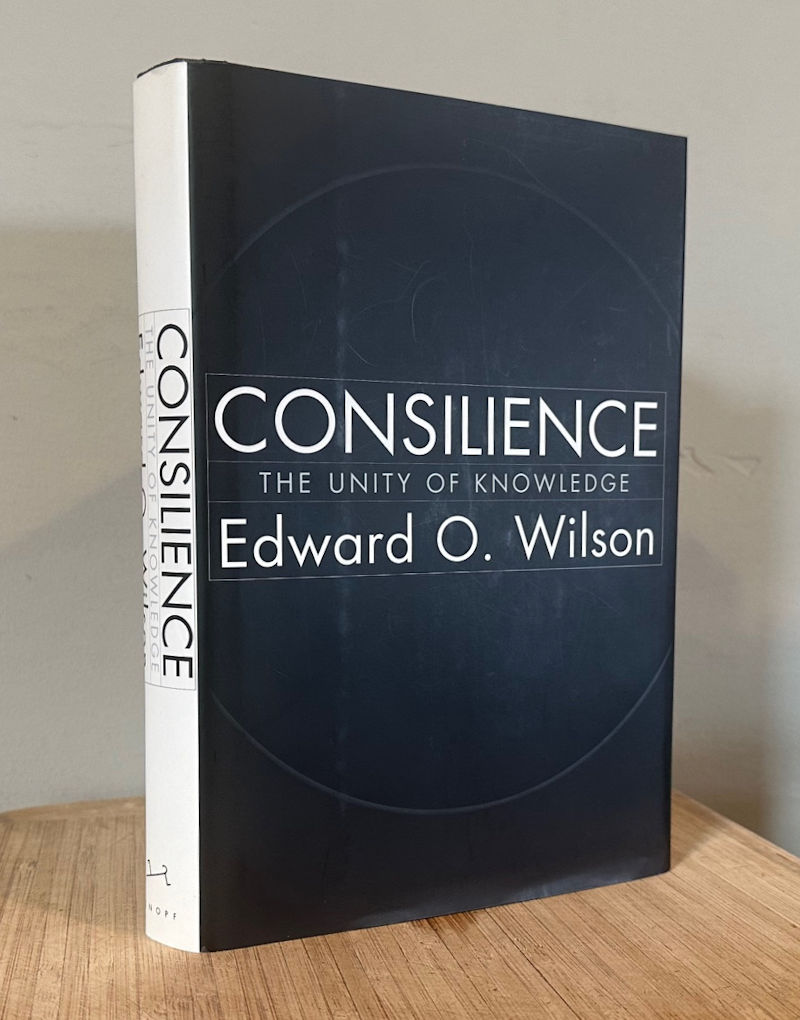

Wilson, Edward O.. 1998. Consilience: The Unity of Knowledge. Knopf. *****

Wilson, Edward O.. 1998. Consilience: The Unity of Knowledge. Knopf. *****

Likely Wilson’s magnus opus, this is his attempt to describe a worldview that unifies all knowledge, especially between the sciences and the humanities, leaving religion behind (as he did as a boy) and applying scientific principles and insights even to areas where this viewpoint is resented. He addresses the great branches of knowledge, and reflects how the Enlightenment was constrained by the deism of its leaders. How science works: “the most effective way of learning about the real world ever conceived.” How philosophy has been hobbled by “ignorance of how the brain works”. How science is challenged by the complexity of systems, with ideas of emergence avoiding the perils of reductionism. His chapter 6 on the mind corresponds to Pinker’s entire book on the subject: the mind is the brain, it evolved for survival and not perception of the real world, and so on. He describes how culture emerges from human nature, and how human nature entails regularities like kin selection and altruism. Then, as Pinker does later, applies these understanding to particular aspects of human culture, especially in the social sciences: the arts and their interpretation, ethics and religion. Finally he asks, To what end? What is humanity’s future? The key questions are: what we are, where do we come from, and how shall we decide where to go. Neither theology nor philosophy has answered these. Our challenges include our potential dependence on prosthetic devices, and our damage to the natural world. He comes down on “existential conservatism”: “The legacy of the Enlightenment is the belief that entirely on our own we can know, and in knowing, understand, and in understanding, choose wisely.” A big book that’s in a sense about everything. Wilson is one of the most graceful and deeply insightful science writers ever. The post here is the 11th, and it links to the earlier 10. (post) (Read Mar 2024)

Nagel, Thomas. 1987. What Does It All Mean?: A Very Short Introduction to Philosophy. Oxford. ***

Nagel, Thomas. 1987. What Does It All Mean?: A Very Short Introduction to Philosophy. Oxford. ***

Very short introduction to the classic problems of philosophy, without historical perspective or mention of particular philosophers. Topics include how we know anything; the mind-body problem; free will; right and wrong; the meaning of life. My key thought as I read this was that science has, in fact, in recent decades, resolved some of these matters, and I wonder to what extent philosophy students are taught that. The problems may be classic, but some of the debates are obsolete. Nagel summarizes the debates, and doesn’t mention science. (post) (Read Feb 2024)

Pinker, Steven. 1997. How the Mind Works. Norton. *****

Pinker, Steven. 1997. How the Mind Works. Norton. *****

Pinker’s second big book after THE LANGUAGE INSTINCT (1994), this one covers many additional topics about the mind. The first part covers evolution and natural selection, and how the mind interprets and understands reality. The second half covers what’s come to be called evolutionary psychology, how interactions between people with minds provides insight into aspects of human cultures. (This part resembles Wilson’s earlier CONSILIENCE.) Key theme: “The mind is a system of organs of computation, designed by natural selection to solve the kinds of problems are ancestors faced in their foraging way of life, in particular, understanding and outmaneuvering objects, animals, plants, and other people.” The mind is what the brain does. Its complex design is genetic. Nature vs nurture is so simplistic as to be not even wrong. Behaviors we think evolutionarily maladaptive (like homosexuality or celibacy) don’t need to be “explained”; they are expressions of minds that formed in our ancestral environment; humans didn’t evolve to spread their genes, they evolved to enjoy behaviors that spread genes. Old notions of souls or force fields have given way to the Computational Theory of the Mind. Evidence for natural selection is overwhelming, despite people desperately wanting it to be wrong. Humans rule over the other animals due to our big brains. There are chapters about how vision works, human reasoning, emotions (common across all cultures), family values (the evolutionary logic of relationships between parents and children, brothers and sisters, men and women, etc.), and a final chapter about “The Meaning of Life,” covering the arts, humor, religion, free will, morality. Perhaps our evolved cognitive equipment, suitable for unconscious survival, is insufficient to understand deep issues. A book both vast and deep, like Wilson’s, it summarizes the modern scientific understandings of almost everything. (Post 1; Post 2; Post 3; Post 4; with a final Post 5 compiling several long quotes from the book.) (Read Feb 2024)

Russell, Bertrand. 1959. The Problems Of Philosophy. Oxford Univ Press. *** 1/2

Russell, Bertrand. 1959. The Problems Of Philosophy. Oxford Univ Press. *** 1/2

A short book about the most basic issues of philosophy: how do we know what’s real? How do we know what’s so? Russell drills through “common sense” notions about these issues to their core meanings. Some of the puzzles Russell examines have been illuminated by discoveries in recent decades in evolutionary psychology, animal perceptions, and the diversity of human cultures. His insights on the value of philosophy are profound: it’s a way of breaking out of what is essentially a conservative mindset and instead contemplating the greater reality outside one’s own interests (in much the way, I would say, science fiction can); the post has a couple long quotes. (post) (Read Jan 2024)

Durant, Will. 2002. The Greatest Minds and Ideas of All Time. Simon & Schuster. ** 1/2

Durant, Will. 2002. The Greatest Minds and Ideas of All Time. Simon & Schuster. ** 1/2

Durant was a well-known historian and public intellectual up until his death in 1981; his major work was the 11-volume THE STORY OF CIVILIZATION, written with his wife. This book is a compilation of various essays, presumably from magazines, amounting to a philosophy fan-boy’s collection of top ten lists. So we get the ten greatest thinkers, ten greatest poets, a hundred best books for an education, and so on. He defends the “great man” theory of history, and his certainty about his choices seems immune from reconsideration (e.g. whether Plato was actually correct or not). At the same time he anticipates Steven Pinker’s later ideas about the progress of morality through the ages. And a quote from Durant’s Wikipedia page reveals his notions about the inevitable decline and rebuilding of civilizations, due to clash between knowledge and mythology/religion. (post) (Read Jan 2024)

Craig, Edward. 2020. Philosophy: A Very Short Introduction. Oxford. ** 1/2

Craig, Edward. 2020. Philosophy: A Very Short Introduction. Oxford. ** 1/2

A small book in Oxford’s “A Very Short Introduction” series. Unlike the Nagel volume, this one does discuss a number of specific philosophers and their arguments, and in a chronological framework. The author considers philosophy’s three big questions to be: What should we do? What is there? and, How do we know? Topics include the Crito of Plato, Hume’s argument about miracles, a Buddhist text about Nagasena; general topics and various “isms”; and “high spots” Descartes, Hegel, Darwin, and Nitzsche. And then free will, and asking, what is philosophy for? (post) (Read Jan 2024)

Frank, Adam. 2023. The Little Book of Aliens. Harper. ***

Frank, Adam. 2023. The Little Book of Aliens. Harper. ***

More pop-oriented than Frank’s previous book, this considers what ordinary people think about the topic of aliens. Usually, UFOs. He outlines the history of speculations about aliens (Drake’s equation, etc.), UFO sightings, SETI, and now UAPs. Then considers how we would find intelligent aliens, if they exist: by looking for biosignatures, and technosignatures, and what those mean. (Attempts to contact aliens via signals, as in Project Ozma, have been largely abandoned.) The substantial recent developments I hadn’t read about in other books concern the results of the orbiting observatory Kepler over the past two decades: it has found planets around virtually every star examined. This has great implications on the results of Drake’s equation. Further, the various systems of planets are never in the same arrangement as in ours, with small rocky planets close to the sun, big gas planets farther out. In passing, Frank notes that climate change may be an unavoidable consequence of developing technology; and how monobiome planets, all water or all desert, aren’t as implausble as I once thought. (post) (Read Jan 2024)